Sometimes Mother’s Day is For “I’m Sorries”

A Local Author recounts her Troubled Father’s Death on Mother’s Day

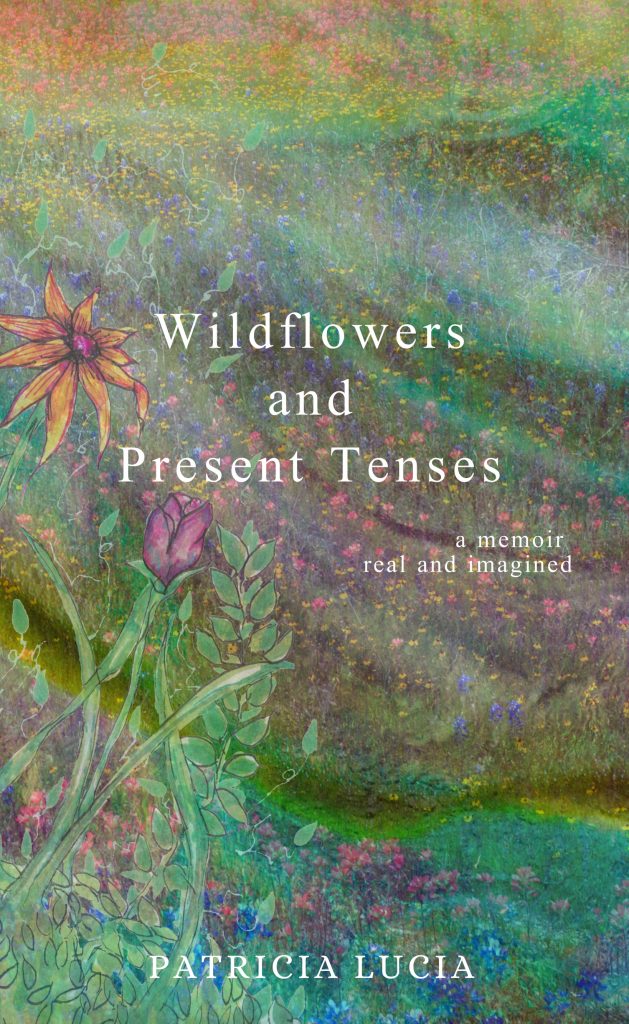

“Mother’s Day” is a New York Times Fellowship award winning short story bylocal author, Patricia Lucia, and was published in her recent memoir, Wildflowers and Present Tenses.

Mother’s Day by Patricia Lucia

Albert rose early that Sunday morning as he always did and, clad only in his Fruit of the Looms, stumbled down the narrow hallway of his trailer home to the small cluttered kitchen. At sixty-nine his legs were still strong and muscled and a little too white beneath his bulky, olive brown body. His hair, still mostly jet black, course and thick, now stood haphazardly about his head and often stayed in this condition until someone – usually a woman – pointed out to him that he had neglected to comb his hair. Albert did not match his clothes either and for years this caused embarrassment for his wife and three daughters at school functions and family outings. He disdained such things. It was hard to live with Albert. But that was more than twenty years ago. Anything could change in twenty years. Even Albert.

He placed two slices of Wonder Bread into the toaster, pushed down the lever and turned on the radio to his favorite Christian station. At 11:00 a.m. James Dobson’s “Focus on Family”, Albert’s favorite talk show, would air. Today Dobson would speak about the most important woman in a man’s life – the mother of his children and keeper of his home. Albert laid out a crisp white shirt and creased pants and sat down to wait for his toast to pop. In recent years, this particular day had become one of the most important days of the year for Albert. A day he could show that a man can change. It was Mother’s Day.

Albert looked forward to a full day. He had a lunch date with Eunice, a lady friend he met at the senior citizen center. At seventy-two, Eunice was small and frail with kind, blue eyes behind her bifocals. She kept her thick white hair in a short no-nonsense cut. Eunice was in most ways a no-nonsense woman. A retired English teacher, Eunice was well read, quick-witted, and independent.

Eunice had taken on the task of tidying Albert’s life. She spent days organizing Albert’s medical and tax files after finding them heaped inside a cardboard box with tools and fishing tackle. Eunice didn’t mind, even delighted in these endeavors. The kind of delight that revealed her love for him. But Albert had declined a romantic relationship with Eunice. He had his eye on a younger woman at the center.

Albert had a few other dates to keep today. Diana, his oldest daughter, had a two year old son, Timmy. He was teaching Timmy how to fish this year. Diana expected him for dinner later. So did Timmy.

Barbara, his third daughter, was a mother of four. He made a point to tell her he was proud of her, words he had not said when she was a child. He was careful to tell her she was a good mother and that he loved her. He had not always been so careful. Only recently had Barbara and his other children, Patricia, Andrew, and Ronald come to forgive him for the mistakes of the past. Those mistakes had cost Albert his family.

Shirley divorced Albert in 1977, after her daughter Patricia, speaking for the five children, had begged her to. Shirley, a devout Catholic, had waited a long time and endured more than even Albert could have expected. Their marriage crumbled years before the divorce, with Albert’s family living on eggshells, tiptoeing around his bitterness and rage. On the afternoon Patricia begged her mother to leave, she had found her mother in the basement weeping over her sewing machine, her tears blotting the cloth beneath the needle.

Albert drank and became irrational and violent. He had an eighth grade education and painted houses for a living. He was self employed and ran his own company. But as the economy in Massachusetts declined, so did Albert. In the end, he turned his rage on his wife.

On New Year’s Eve in 1972, Albert, high on alcohol and tranquilizers took Shirley home from a relative’s party and beat her until she lost consciousness. Shirley managed to crawl into her son’s room and into the lower bunk where her youngest son shivered. She stayed there for a week. In the hushed days that followed, Diana and Barbara brought her soup and aspirin and helped keep her steady when she began to walk again. Patricia cleaned her mother’s blood from the kitchen floor and from the dent made by her head in the living room wall. She never entered the room where her mother lay. Instead, Patricia assisted her father in renovating the bathroom. Albert’s apology. Sensing the urgency in such an apology, she exerted every bit of her eleven year old strength in cleaning, hammering, lifting, and measuring his apology.

Shirley eventually accepted Albert’s apology but their marriage never recovered. Albert didn’t beat her again, but he never recovered either. He found fewer jobs, drank more and grew more bitter. In the autumn of 1976, after Patricia’s plea in the basement, Albert lost his family. He moved into a trailer park close by and spent his days fishing and drinking.

Now, twenty years later, Albert looked forward to each holiday. Mending times. He sent cards and called on the birthdays of his grown children. He gave them a little money at Christmas if he had it. He insisted on picking up Patricia at the train station when she traveled from New York City and sometimes slipped a crumpled twenty dollar bill into her palm when he said good-bye.

He and Shirley became friends again, speaking on the phone on occasion, usually about the children. He called her on holidays and most importantly on Mother’s Day. After all, Shirley had done her best. Feeding her children on the meager rations he had given her. Making the most of hand me downs. Walking the desperately thin line between protecting her children and honoring her husband. Forgiving him again and again. Mother’s Day gave Albert a chance to tell her how grateful he was. And how sorry.

Albert liked his toast dark. The smell of toast wafted into the living room long before the toaster clicked and snapped. Albert didn’t smell the toast nor hear the toaster pop. Here, on the van seat he used for a couch, with his brown hands folded on his lap and his ankles crossed like an expectant schoolboy, Albert had slipped away forever.

Later, Eunice, disappointed and a little hurt, called and left a message on Albert’s machine, careful that her voice did not give away the slight wound.

Barbara wondered, after putting the kids to bed, why her father had forgotten to call. Diana cleared away his place at the dinner table and assured Timmy that Grandpa would visit tomorrow. Shirley, now happily remarried, did not think of Albert’s omission until the next day when Diana called from his trailer.

I received my call at 4:00 that Monday afternoon. My mother’s words came slowly,unsteadily.

“Pat,” she said. That is what she had always called me, except for those occasions when, as a child, I was in serious trouble. “Pat” is how she addressed me that afternoon long ago in our basement. “I’m so sorry to have to tell you this – ” Her voice failed. But I knew across the miles of phone lines between my New York apartment and her home in Springfield that my father was

gone.

I met Eunice for the first time at my father’s wake. She kept vigil for two days by his casket, with her hands loosely clasped, her head unbowed, her eyes patient and unblinking, occasionally straightening his tie and finally combing his hair just before the heavy wooden door closed.

My father had shown Eunice pictures of his children. She had memorized our names. “You’re Pat,” she said, then after a moment, “Your father was a good man, Pat.” Her moist eyes searched my face. I nodded, unable to keep her gaze.

Patricia Lucia lives in South Florida and is a high school English teacher, author and public speaker. “Mother’s Day” and other short stories were published in her memoir Wildflowers and Present Tenses, released in November 2020. Visit pattiluciawrites.com for more information.

Media Contact Details

Patti Lucia, Patti Lucia Writes

lake Worth, USA

(561) 962-0140